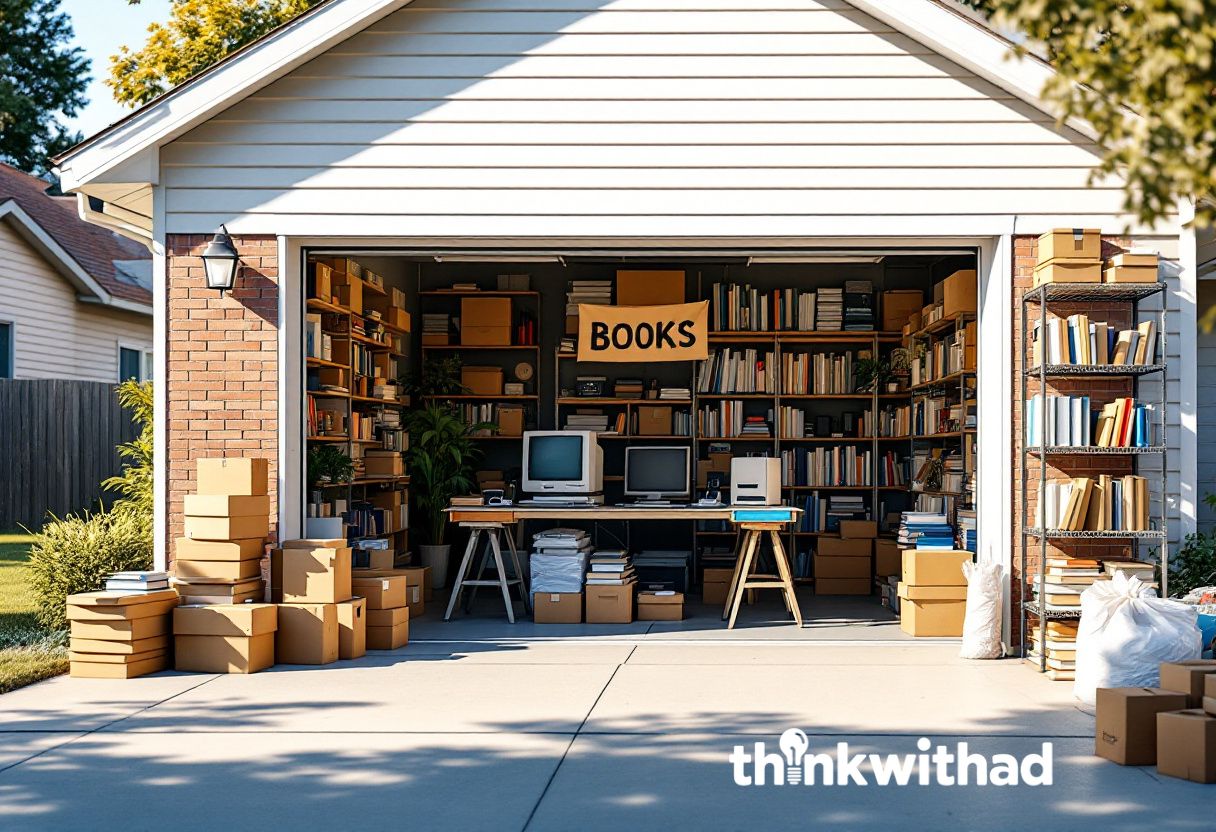

Built in a Garage: How Scrappy Starts Became World-Class Companies (and the Moves You Can Copy)

Why these stories still matter

A garage isn’t glamorous—it’s rent you can afford and excuses you can’t. The teams you know didn’t wait for corner offices or perfect funding. They worked inside tight constraints, solved one real problem for one real customer, and shipped. Then they did it again.

HP landed Disney as an early buyer for a humble test instrument. Apple took a purchase order before they had proper furniture. Amazon stacked door-desks and mastered one category before adding the next. Google rented a small Menlo Park garage and made search so useful that word of mouth did the marketing. Disney cut reels in a borrowed space and turned consistency into leverage. Yankee Candle began with a handmade gift and a neighbor’s cash that funded the next two. Harley-Davidson reworked an underpowered prototype until it climbed real hills. Mattel pivoted from picture frames to dollhouse furniture when customers voted with their wallets.

Different eras, same rhythm: specific problem, simple solution, fast iteration, proof in the wild. That’s repeatable—today. Here’s what they actually did in those early rooms and how to use the same moves now: land one credible buyer, ship weekly, document your system, and upgrade only when your process outgrows the space.

HP (1939): Two engineers, one garage—and a film studio that said yes

Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard rented a one-car garage in Palo Alto and built an audio oscillator rugged enough for professional sound work. Walt Disney Studios bought early HP oscillators for Fantasia—not a headline, a purchase order. That tiny sale proved their gear could perform in the real world. From there they built around pragmatic engineering, customer trust, and a culture that treated documentation and iteration like oxygen.

Use this now: Build one tool for one pro job; land one credible customer; let performance be the marketing.

Apple (1976): A purchase order before the company even had furniture

Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs assembled Apple I boards at the Jobs family home in Los Altos. The break was a Byte Shop order for 50 fully built boards—real money, real deadline. To finance parts, they negotiated short supplier credit and moved fast. The “garage” mattered less than the loop: prototype → sell → professionalize. That cycle carried them from hobbyist boards to full systems—and built the muscle to scale.

Use this now: Don’t wait for pristine financing; fulfill one real order well; turn it into a repeatable build checklist.

Amazon (1994): A narrow thesis, door-desks, and relentless standards

Jeff Bezos chose books first: massive catalog, standardized listings, clear demand. He coded, taped boxes, answered emails, and worked off cheap door-desks—a signal to spend where customers feel it. Three promises—speed, accuracy, support—became muscle memory. Trust created volume. Volume funded logistics, Prime, and eventually cloud. The lesson isn’t “be Amazon.” It’s “be undeniable at one thing, then earn the right to do two.”

Use this now: Pick a wedge where you can be the best; make three promises you always keep; invest in unglamorous details that raise confidence.

Google (1998): Rented garage, world-class search

Larry Page and Sergey Brin set up in Susan Wojcicki’s Menlo Park garage and focused on a single outcome: the most relevant result, fast. The product was obviously better; usage grew by word of mouth. They moved from clever prototype to daily habit because their core engine improved every week. Throughput beat headcount, and iteration speed beat bigger budgets.

Use this now: Choose one metric that defines “better” (speed, relevance, uptime); improve it weekly; let usage pull you forward.

Disney (1923): A borrowed garage becomes a studio—and a reel becomes a future

Walt and Roy Disney worked from a relative’s garage in Los Angeles while producing the Alice Comedies, hybrid shorts mixing live action and animation. The reels weren’t perfect; they were consistent. That consistency secured distribution, earned a modest office, and built a delivery cadence long before features and theme parks. Discipline—not equipment—did the heavy lifting.

Use this now: Make a compelling “proof reel” (demo, sample, case study); ship on a cadence; upgrade space only when the process demands it.

Yankee Candle (1969): One gift, one neighbor, one line out the door

At 16, Mike Kittredge melted crayons to make his mom a candle. A neighbor bought it on the spot. He used that cash to make two more. Word spread from kitchen counters to a small shop to a national brand. There was no master plan—just reinvestment, friendly service, and listening closely to what buyers wanted next (sizes, scents, seasons).

Use this now: Sell one unit to one real person; roll proceeds into the next batch; let customer requests pick your next SKU.

Harley-Davidson (1903): A 10×15-foot shed and a bigger engine

William S. Harley and Arthur Davidson started in a tiny wooden shed in Milwaukee, hand-building their first motor-bicycle. Version one struggled on steeper hills. They did the unglamorous thing that wins: re-engineered the engine, tested again, and kept iterating. By 1906 they moved into a modest factory; community formed around a machine that performed.

Use this now: Ship a version that works, measure where it fails, and upgrade the core—not the paint job. If your “engine” (product, offer, ops) is underpowered, fix torque before you polish the tank.

Mattel (1945): Frames in a garage, toys from the scraps

Harold “Matt” Matson and Elliot Handler started in a Los Angeles garage making picture frames. They used leftover frame wood to craft dollhouse furniture, and the “side product” started selling better than the frames. Ruth Handler joined, they leaned into toys, and the company scaled from garage runs to cultural icons by following demand, not ego.

Use this now: Watch what customers actually buy—even if it wasn’t your “main” idea. Double down on the sleeper hit, sunset the rest, and rebuild your process around the thing that’s pulling on its own.

The patterns winners share

- Specific > broad. Each story begins with one precise job to be done.

- Constraint as a feature. Cheap, tight spaces killed distraction and forced output.

- Proof over polish. Real customers beat long slide decks.

- Cadence beats drama. Weekly improvements compound into a moat.

- True story = brand. Honest origin stories convert because they’re useful, not theatrical.

Your 2-week “garage” sprint (wherever you work)

- Day 1: Pick one customer type + one problem you can solve this week. Write it in one sentence.

- Day 2–3: Build the smallest thing that works. No extras.

- Day 4: Put it in front of 10 real prospects. Ask for a yes/no and one sentence of feedback.

- Day 5–7: Deliver to whoever said yes. Document the steps.

- Week 2: Turn that delivery into proof (short video, case study, testimonial). Repeat with one improvement.

Run this loop twice and you won’t need a garage story—you’ll have a traction story.

🧠 ThinkwithAD – PULSE

Real-world playbooks for growth—money, mindset, and moves that actually land. Urban lens, professional execution. No filler—just strategy.

⚠️ Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes and general information. Company histories are summarized from well-documented public records; timelines and details are presented accurately to the best of our knowledge at time of writing. Always do your own research before making business decisions.